Computational mixology

Since last year I am following a culinary course, with a module on cocktail making. Since classes are presently canceled due to the ongoing pandemic, I have taken a more theoretical approach to the subject. Last week, I presented some ideas and findings on the (data) science of mixology for our department's science café. You can find my slides here. This post is a novelization of the talk.

Cocktails and how to model them

For a definition of a cocktail, as always look no further than Wikipedia:

A cocktail is an alcoholic mixed drink, either a combination of spirits, or one or more spirits mixed with other ingredients such as fruit juice, flavored syrup, or cream.

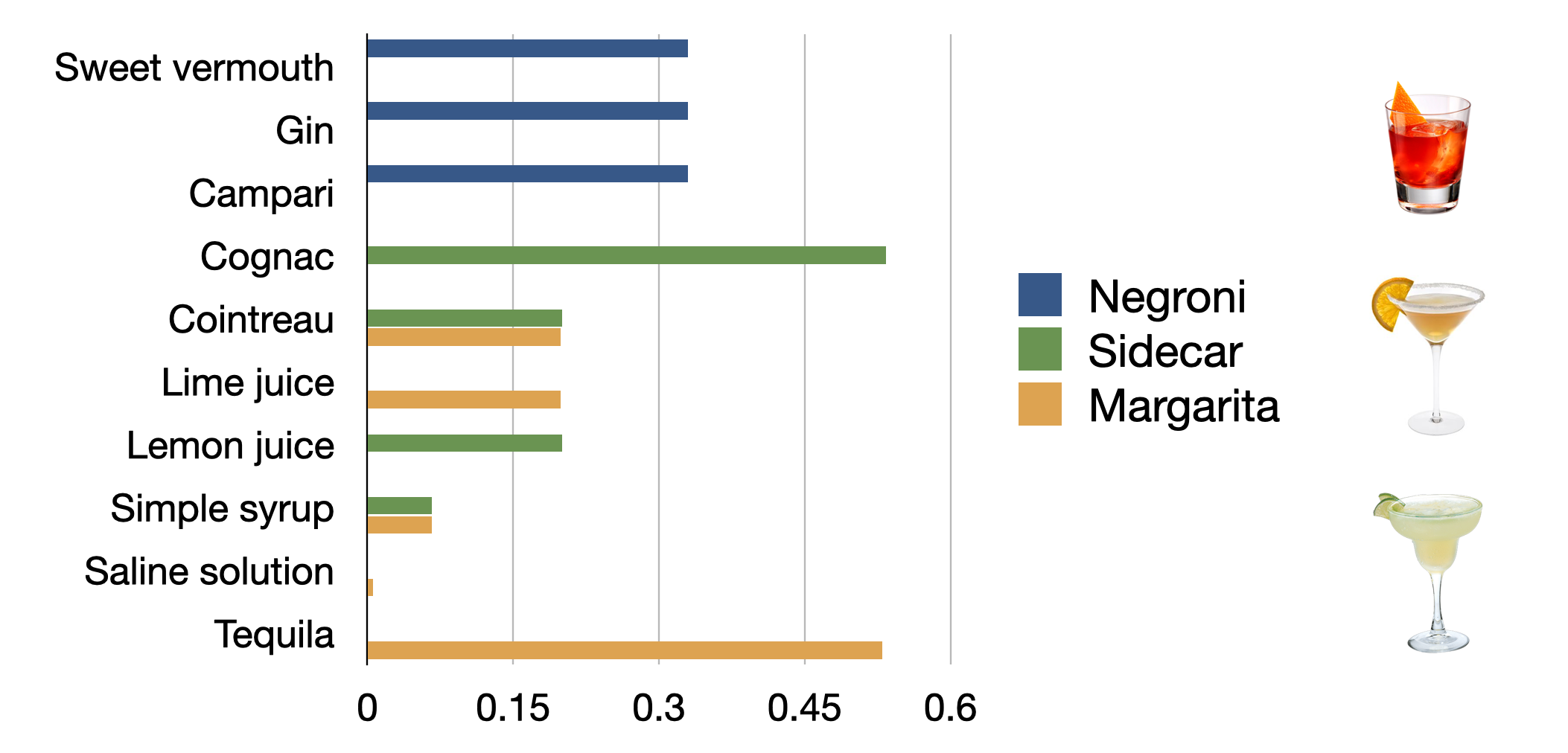

So cocktails are mixtures of several beverages (the mixers), where at least one has to be alcoholic. Sorry, teetotalers. As most recipes contain the volumes of the mixers, it is sensible to just normalize the quantities by total volume. The critical bit of information is hence the volume fraction of each ingredient.

So cocktail recipes are compositional data, and we have to analyze them as such. There are hence three essential aspects to a cocktail recipe:

Which mixers are we going to choose?

In which ratios are we going to add the mixers?

How are we going to mix the cocktail?

The fundamental law of traditional cocktails

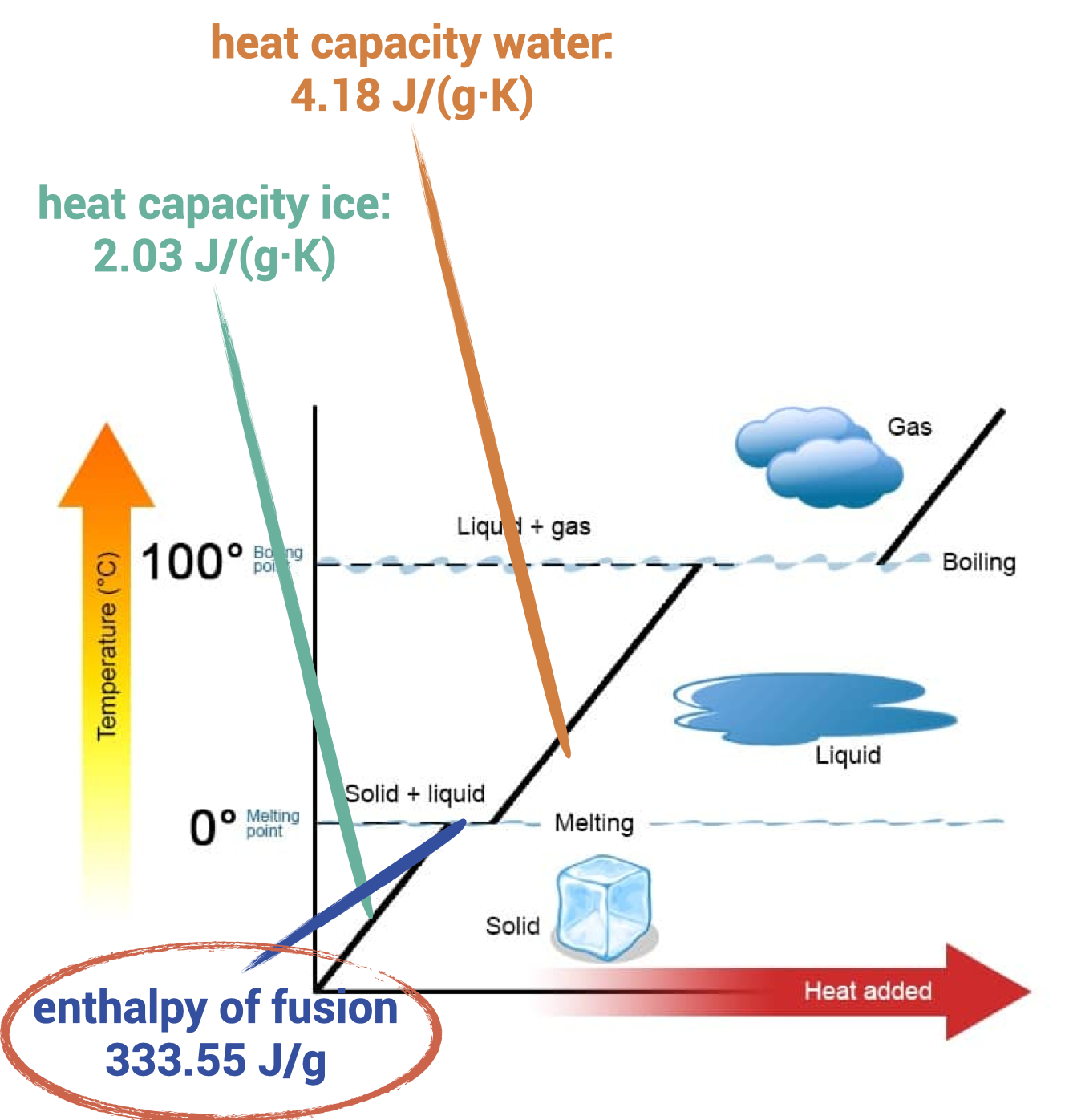

Traditional cocktails are cooled by using plain ice[[nontrad]]. They are either stirred, shaken, with or without egg-white, blended, or just served with an ice cube. It is illuminating to look into the thermodynamics of water to understand how ice cools a cocktail.

So, there are three ways how ice can cool the cocktail:

ice absorbs heat, increasing its temperature, the accounts for 2.03 J/(g·K);

cold water obtained from molten ice increases its temperature to the cocktail equilibrium temperature, this amounts to 4.1814 J/(g·K);

ice melts absorbing a whopping 333.55 J/g.

Clearly, most of the cooling is not due to cold ice becoming warmer ice. Cooling is primarily due to the melting of ice! This is even more pronounced when you consider that you typically take ice from the freezer (-18 °C) into an ice bucket, where it rapidly becomes melting ice (0 °C). This motives the fundamental law of traditional cocktails:

There is no chilling without dilution, and there is no dilution without chilling. – Dave Arnold

Some important conclusions can be drawn from this law:

You can standardize cocktails by measuring their temperature. Just mix until they have the required temperature, and you are guaranteed to have the optimal dilution of the ingredients.

The shape of the ice (cubes or crushed) does not matter. Smaller chunks of ice will cool and dilute faster, but you can still attain the same cocktail regardless.

Always use ice to cool, not plastic ice cubes as these cannot melt[[melting]] and are hence inefficient cooling agents.

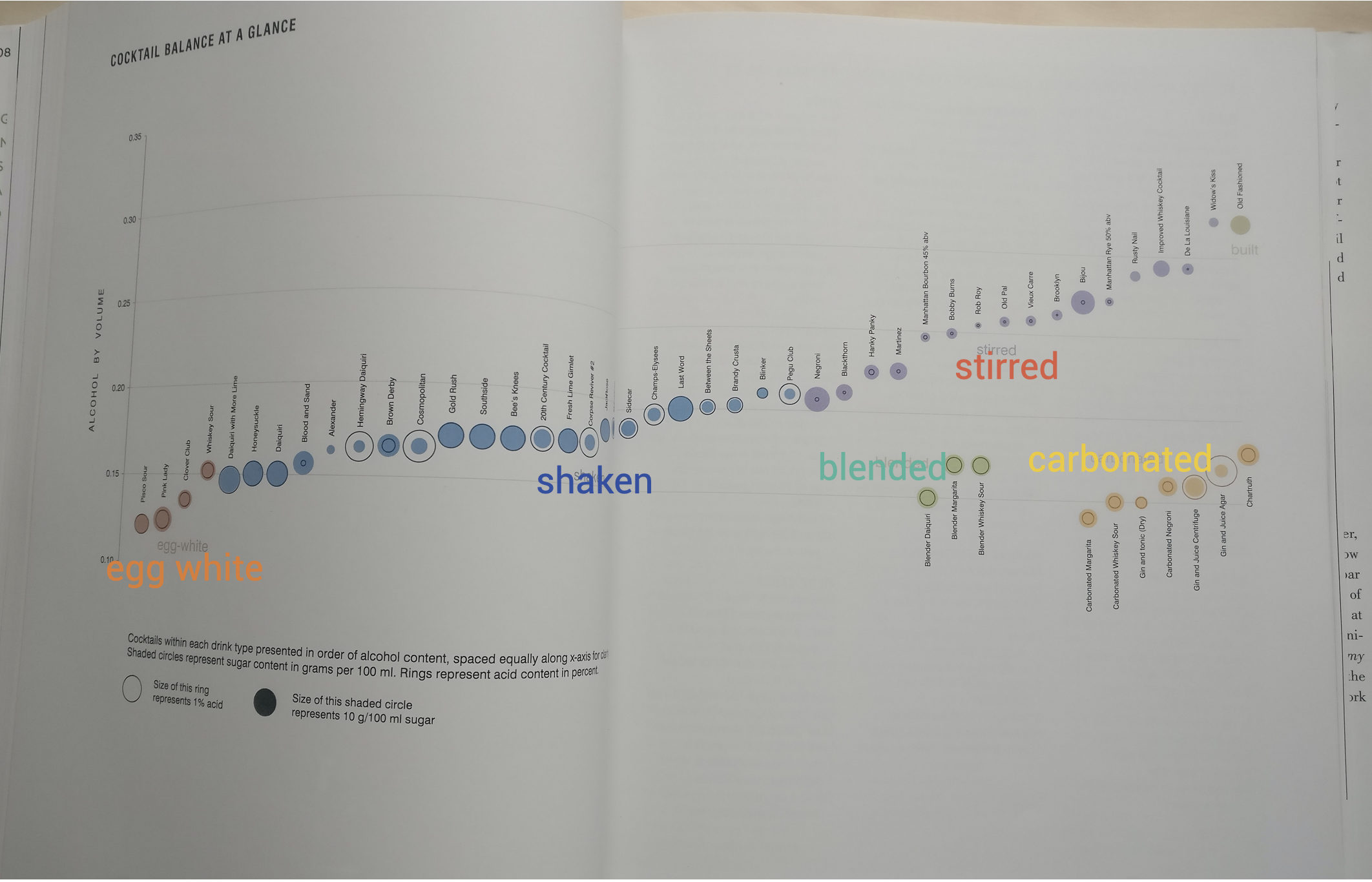

The fundamental law has significant consequences on how cocktail recipes are designed. Consider the different ways of mixing a cocktail.

Simple built cocktails are mixed less intensively compared to stirred or shaken cocktails. Blender cocktails are mixed the strongest. More intensive mixing means more cooling and dilution, which again implies a different recipe composition. Dave Arnold has analyzed 54 well-known cocktails for their alcohol content, acidity, and sugar content.

So the type of mixing has a profound influence on the mixer ratios. Let us take a closer look at the numbers!

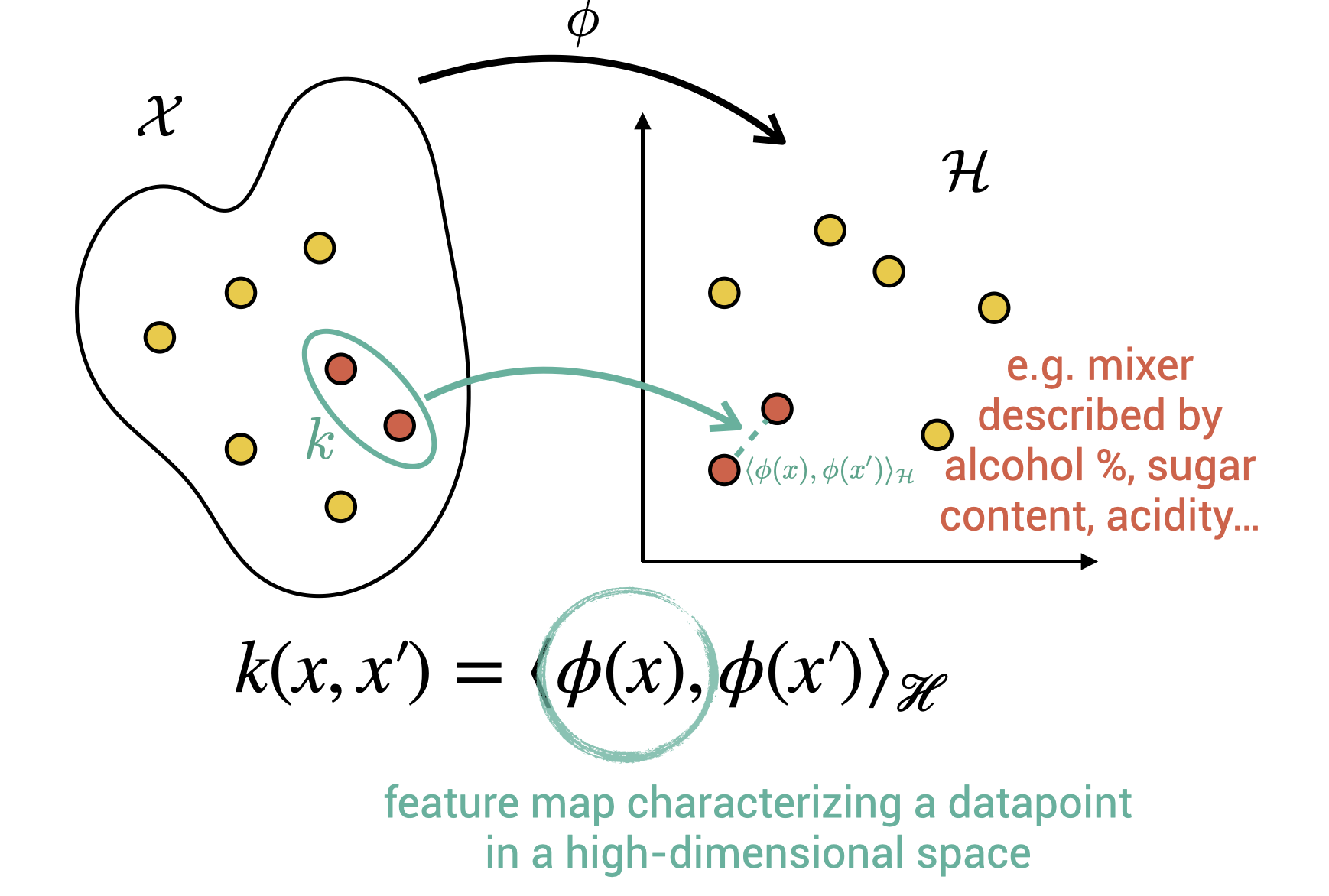

Cocktails in the Hilbert space

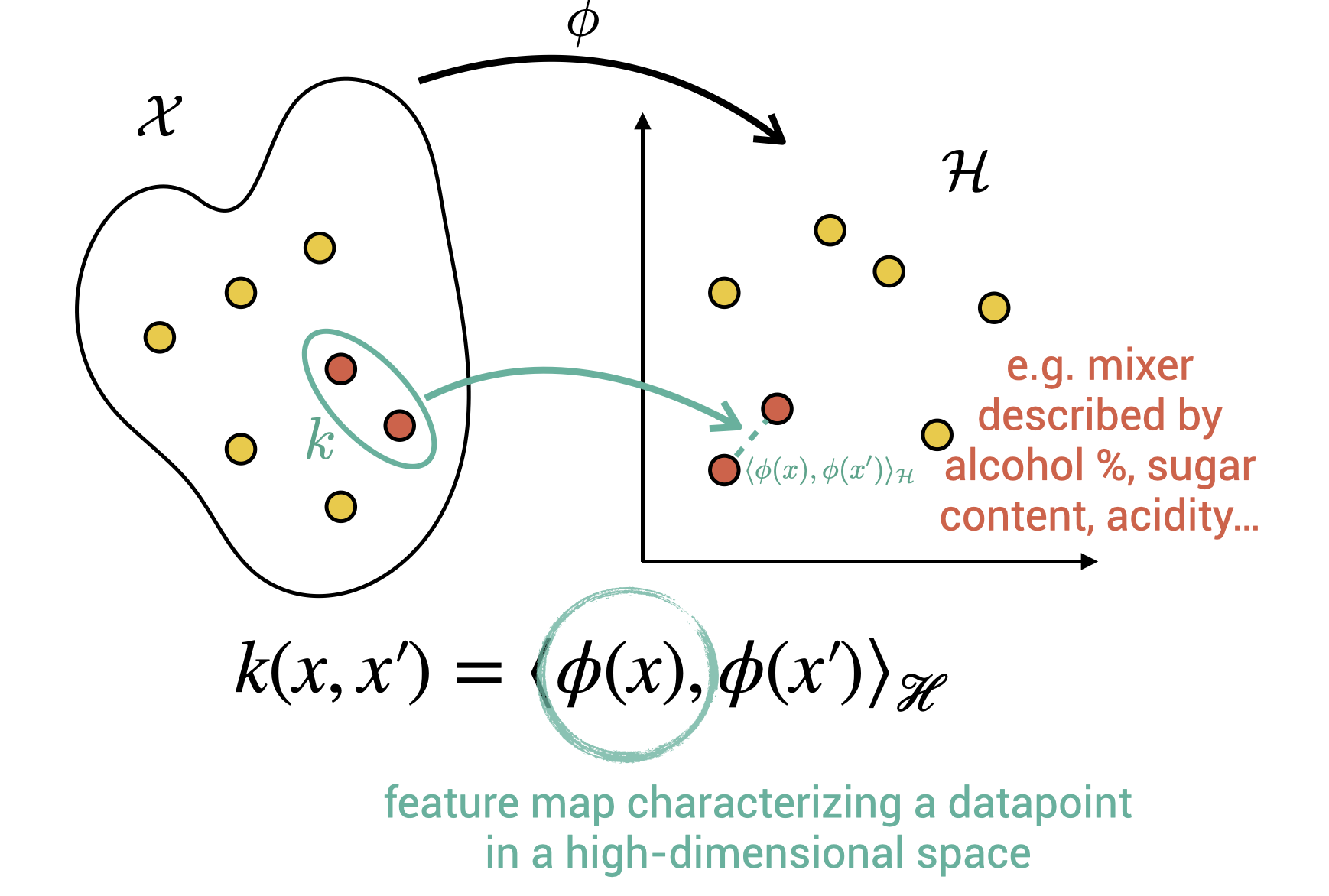

Given that there is not a lot of cocktail data but that we expect there to be a nonlinear effect on how the mixers interact, kernels seem an appropriate tool! Without losing ourselves into the details, kernels are a way to represent data points in a high-dimensional Hilbert space. Think of a mixer, which can be described by alcohol and sugar content, acidity, type (liquor, sweetener, etc.). We can think of a feature map where we perform a nonlinear expansion of all these variables, projecting the mixer in a high-dimensional space. A kernel function is used to implicitly define such space. It represents a dot product in this space.

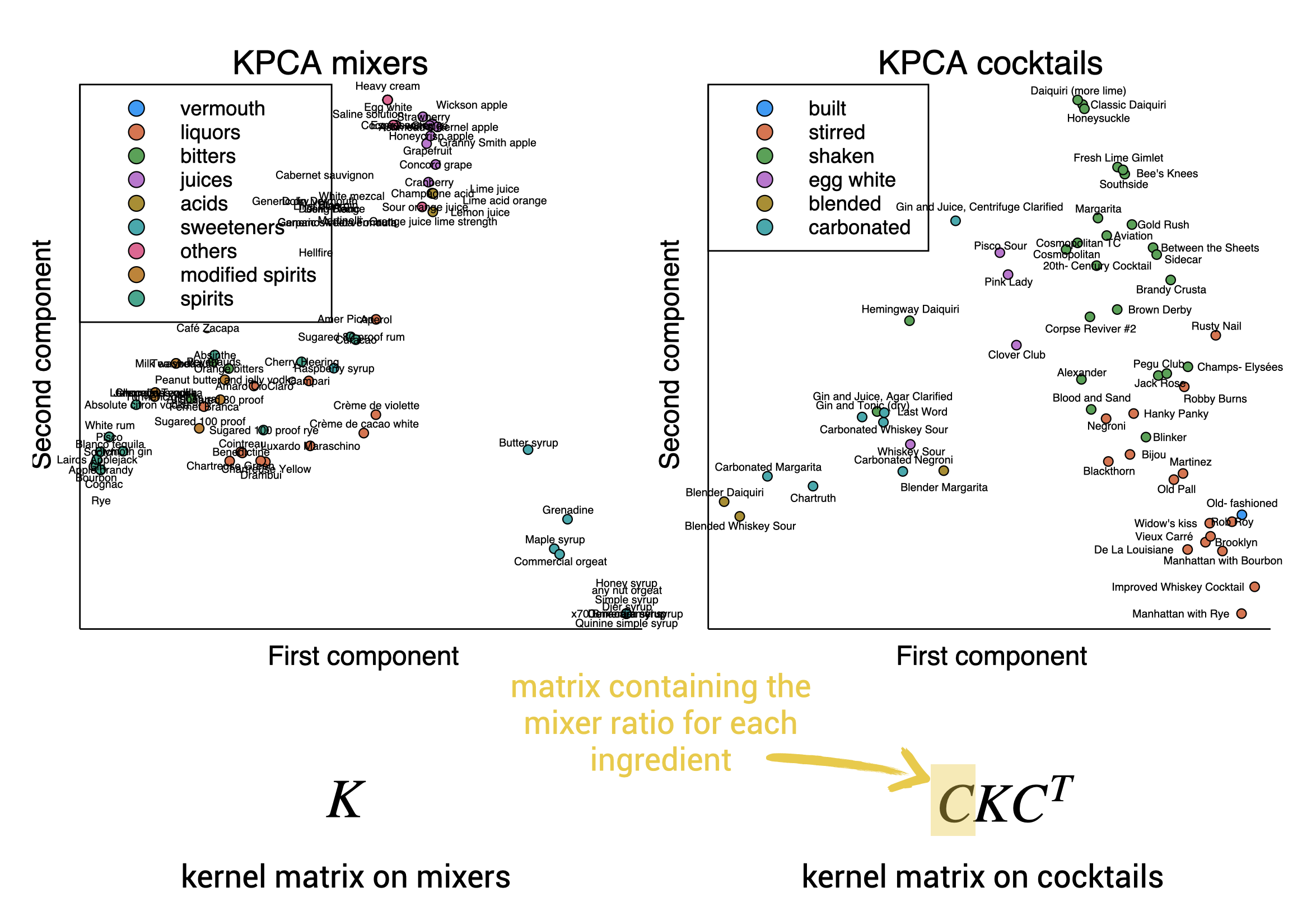

Kernels are hence a clever way to represent the mixers in a Hilbert space. How can we take a look at this space? Using PCA allows us to project back into two or three dimensions.

We now can describe the mixers, how to represent the cocktails. To this end, we can use kernel mean embedding, an elegant framework to represent probability distributions (i.e., compositions) in the Hilbert space. The idea is as smart as it is simple, to embed a cocktail, just take the weighted sum of the embeddings of the mixers:

where we have:

: the representation of the cocktail;

: the representation of the th mixer;

: the volume fraction of the th mixer.

But, you might wonder, a linear combination might not possibly suffice for representing the complex interplay between the mixers that constitute a cocktail recipe? This is the magic of kernels because we work in a high-dimensional space, linear combinations in that space can capture intricate, nonlinear patterns! It can be shown that for various commonly-used kernels, the kernel mean embedding is injective: all information about the composition is retained!

Let us take a look into the Hilbert space of mixers and cocktails.

Looking pretty good! We have successfully represented cocktails as points in a Hilbert space. Note that the cocktails cluster quite well by type of mixing. Such a vectorial description can be used as a fruitful basis for all kinds of supervised and unsupervised data analysis!

Designing cocktails as an optimization problem

Can we use the data to design new cocktail recipes? I outline two straightforward approaches: the easy problem of determining the fractions for a recipe and the harder challenge of creating new recipes.

Easy: determining the fractions of a recipe

Suppose you have a recipe with mixers and you want to determine the volume fractions to obtain a cocktail similar to one of embedding . This might be a particular cocktail or an averga over a class. To find the volume fractions, one has to solve the following optimization problem:

Here means the simplex, i.e., all vectors of length where the elements are nonzero and sum to one. Hence, all valid composition vectors. The first part of the objective is a data-fitting term we have to match. The second part is a regularization term, with the information entropy. Good things can come by using this regularization. For example, it will drive the solution to use all mixers, which is desirable. Importantly, the entropic term will make the problem strongly convex. Hence, simple gradient-based methods can be used to find the solution efficiently. So, if you want to tweak a cocktail recipe by, for example, exchanging lime juice by lemon juice, the above optimization problem can help you adjust your recipe!

Hard: designing a recipe from scratch

A slightly different setup: given a liquor cabinet of mixers , select a subset of mixers and find the mixing ratio vector to obtain a cocktail similar to embedding . So we first have to select which mixers to use before we can determine the volume ratios. I propose the following optimization problem:

The data-fitting term is the same, but instead of using entropic regularization, we use the zero-norm. This norm will induce sparsity, thus selecting only a subset of the available mixers. This is quite a different beast compared to the previous problem! It is akin to the knapsack problem and is an NP-hard problem.

Conclusion: tweaking a recipe is easy, inventing it is hard!

Digestif and further reading

Cocktails, and by extension, food science, lead to compelling problems of modeling and optimizing of compositional data. I find kernel methods particularly appropriate for these types of problems, and I like how they lead to elegant formulations.

If you are interested in cocktails, I enjoyed reading the following works:

'The Joy of Mixology' by Gary Regan, an excellent introduction to bartending;

'Liquid Intelligence' by Dave Arnold, discussing the fundamental law of cocktail making and many interesting aspects in the science of cocktails;

'Cooking for Geeks' by Jeff Potter, not specifically about cocktails but an excellent read for every scientist who likes cooking.

A word of warning: reading these books might lead to some unintended additional purchases!

If you are the rare person interested in kernels, and how to use them for distributions, you might check the following works:

Muandet, K., Fukumizu, K., Sriperumbudur, B., & Schölkopf, B. (2017). Kernel mean embedding of distributions: a review and beyond. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning, 10(1–2), 1–141. Retrieved from

Kanagawa, M., Hennig, P., Sejdinovic, D., & Sriperumbudur, B. K. (2018). Gaussian Processes and kernel methods: a review on connections and equivalences.

Van Hauwermeiren, D., Stock, M., Beer, T. De, & Nopens, I. (2020). Predicting pharmaceutical particle size distributions using kernel mean embedding. Pharmaceutics 2020, Vol. 12, Page 271, 12(3), 271.

(Yes, I shamelessly added our recent work in using kernels for modeling pharmaceutical distributions.)

We made an elegant alternative model to determine the mixing ratios for cocktails using convex optimization, but this will be something for another post!